The history of United States government markers to identify the graves of those who served in the armed forces extends to frontier days prior to the Civil War. Soldiers who died were buried, chiefly within post reservations, with a wooden board as a "headstone." Over time, these boards became standardized in style, and in 1861, shortly after the beginning of the Civil War, the War Department assumed responsibility for military burials and for marking graves. The Quartermaster General of the Army was directed to provide headboards.

With a short life expectancy, these wooden headboards were soon recognized to be too costly to maintain and replace for the estimated 300,000 recovered dead of the Civil War. Proposed alternatives were marble and galvanized iron; the debate between these went on for years, and not until 1873 was marble finally adopted. This "Civil War" type of monument (left) is of white marble, 10 inches wide, 4 inches thick, and long enough to allow 12 inches above ground. For Union soldiers (only), there is a sunken shield with the inscription in relief, including the soldier's name and unit designation, and sometimes a rank or duty assignment, but without dates. The family could have dates engraved locally at their own expense, of course. (Edgar Allen, who lived from 1838 to 1904, was a horse and wagon driver in the Civil War, and is buried in the Lower Amherst cemetery.)

The Civil War type of headstone was retroactively furnished for Revolutionary War dead, for those who died in the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, and, after the end of the Spanish American War, for the dead of that war as well. A review in 1902 resulted in a decision to increase the width of the stone to 12 inches and the height to 39 inches.

In 1906 Congress authorized furnishing stones for Confederate soldiers; a design similar to that for Union soldiers was adopted, but having a pointed rather than rounded top, and without the shield (left). These are rare in our area. Thomas Parker (1815-1884), who served in the Alabama infantry, is buried in Riverside Cemetery, Iola.

After the First World War, a board of army officers adopted a new design (right) to be used for all graves except those of veterans of the Civil and Spanish American wars. These were 42 inches high, 13 inches wide, and 4 inches thick, and weighed approximately 230 pounds. The incised inscription on this "General" type of stone included the name, rank, regiment, division, date of death (but not date of birth), and home state. These headstones are still available today, although seldom requested except as replacements or for installation in military cemeteries, such as the one at King, Wisconsin, where they are required. (John Bella, whose headstone in St. Casimir's cemetery is shown here, was a World War I veteran from the Town of Dewey.) Light gray granite has been accepted as an alternative to marble since 1941.

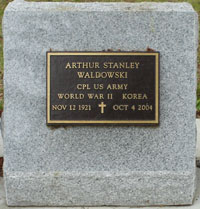

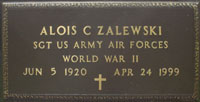

Headstones and markers issued today (left) include full information if requested. Information that may be carved at government expense includes:

- Mandatory Items: Name, branch of service, year of birth, and year of death.

- Optional Items: Month and day of birth, month and day of death, highest rank achieved, awards, war service, and emblem of belief.

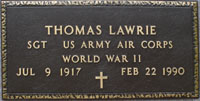

Branches of service are US Army, US Navy, US Air Force, US Marine Corps, US Coast Guard, and two services which no longer exist, the US Army Air Corps (USAAC) and the US Army Air Forces (USAAF). The Merchant Marine has also been recognized.

In addition to the plain Christian cross, there are no fewer than 47 other emblems of belief, including one for atheists. Many variants of the plain cross (Methodist, Lutheran, Russian Orthodox) can be found in Portage County. As noted above, an emblem of belief is optional. Gallery of emblems

War service includes active duty during wartime; present rules do not require the individual to have served in the place of war. For example, when the inscription "Korea" was authorized in 1951 it was limited to those who had died in, or as a result of service in, Korea. But since 1964 the inscription "Korea" has been authorized for anyone who was in active service at the time of the Korean War; it does not therefore necessarily mean that the person served in Korea. Similarly, those in active service at any time between August 5, 1964 and May 7, 1975 may have the word "Vietnam" on their markers, whether or not they were ever in Vietnam.

"World War I" was not engraved for veterans of that war until after World War II. (See John Bella's headstone, above.) World War II was our last officially declared war; thus we have "Korea" and "Vietnam" and not "Korean War" or "Vietnam War." We also have such inscriptions as "Berlin Crisis", "Persian Gulf", and "New Guinea", as well as "MIA" and "POW."

Awards frequently seen are the Bronze Star Medal (BSM) given for heroism or for meritorious achievement in ground combat, and the Purple Heart (PH), instituted by George Washington in 1782, given to those wounded or killed in action. Either decoration, as well as others, may be accompanied by one or more Oak Leaf Clusters (OLC), which show that the award was merited additional times. Thus, "PH & 2 OLC" would signify that wounds were received on three occasions. The Silver Star (SS) recognizes gallantry in action. Flyers may receive the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for heroism or extraordinary achievement in aerial combat. U. S. Navy and Marine Corps medals include the Distinguished Service Medal and the Navy Cross. Many other military awards exist.

Here shown in white marble (right), but which may also be furnished in light gray granite, this familiar style of grave marker was adopted on August 11, 1936. It is 24 inches long, 12 inches wide, and 4 inches thick, and weighs about 130 pounds.

Also measuring 24 inches long by 12 inches wide, the now common bronze plaque (left) was adopted on July 12, 1940. It is an alternative to the stone markers of the preceding paragraph, which continue to be available to this day. The original design (upper) was borderless; some of these lack a date of birth, which was not authorized to be included on military markers until 1944. A revised design (lower) was approved in 1972 and replaced the earlier form. It is indeed made of solid bronze, and is surprisingly heavy: 18 pounds. This plaque can be set in concrete (not paid for by the government, nor are any costs of installation of government markers and plaques), or it can be mounted in a number of ways. It is often seen attached to the back of a privately furnished headstone. Caveat: Where both private and military markers exist, the dates do not always agree! Examples

Called a "niche marker" (right), this 8½ by 5½ inch bronze plaque is now available only for those whose deaths occur on or after September 11, 2001. It may be used if entombment is in a mausoleum, or to supplement a private monument. It weighs about 3 pounds.

As is the case with government publications, the design of government military plaques is not copyrighted. Private monument companies are therefore free to copy them, and they do, in a profusion of variations. These "military-like" stones and plaques are often sold as matching markers for spouses of veterans and are commonly seen everywhere. As a matter of fact, military grave markers are made by the same monument companies that provide private markers; the only real difference is that military markers are billed to the government.

Cenotaphs: The words "In memory of" on a government-provided military marker always indicate that the person's remains are not buried at the site. In this case the words "In memory of" are mandatory. The government will not inscribe these words when remains are buried. Caveat: Survivors can have a military-like marker created with anything they wish on it, if they pay for it themselves. Therefore, one should not be too hasty to conclude that a "military" marker is a cenotaph.

The Air Service was officially recognized as a unit of the U. S. Army in 1918. On July 2, 1926, Congress renamed this unit the Army Air Corps, under which it continued in the period between the World Wars, until it was renamed again as the Army Air Forces on June 20, 1941. Since this was before Pearl Harbor and the U. S. entry into World War II, all army personnel in that war who were assigned to aviation units were in the AAF. Nevertheless, the AAC designation frequently appears on military markers for World War II veterans. However, references to "US Air Force World War II", as are sometimes seen, are decidedly anachronistic, because the U. S. Air Force did not exist as a separate branch of service until September 17, 1947, two years after the end of the war.

Some abbreviations commonly encountered on military plaques include: